Concert of the week in Grateful Dead history: April 5, 1971 (Listen Now)

Goin’ down the road feelin’ bad. Don’t wanna be treated this a-way.

By The Deadhead Cyclist

For Week

15

Deadheads invariably have a great story about the moment they knew they were a Deadhead. For most, it was the first time they saw the band live, but for me the magic moment arrived a full four months before my first show. It was the Summer of ’74. I’d returned home from my sophomore year at UCLA, ready to spend the summer working at a day camp, saving money, and partying with my high school friends, who had scattered to various colleges in a virtual teenage diaspora.

My experience during my two years at UCLA had atrophied steadily from enthusiasm to disappointment to depression. Having gone to high school in Anaheim, going to college just 40 miles up the interstate seemed as smooth a transition as the one I was about to discover on the Dead’s “Skull and Roses” album. Aside from the joy of playing my saxophone in the UCLA jazz band, while watching the Bill Walton-led Bruins basketball team defeat a succession of victims on their way to another NCAA championship, I was “feelin’ bad” and itching to be “goin’ down the road” (or, more accurately, up the road, as it turned out).

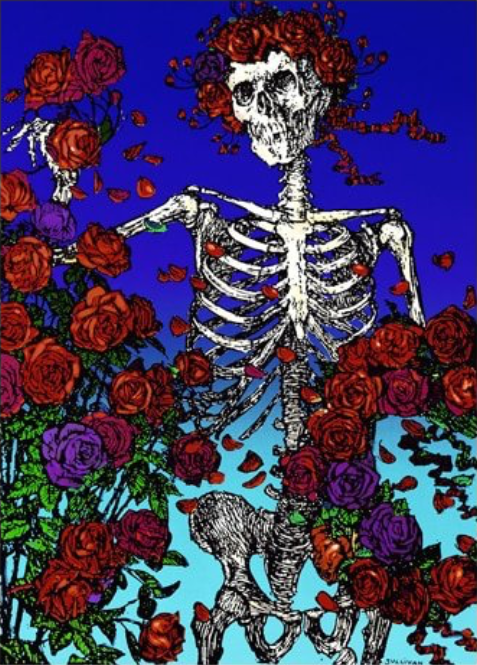

My best friend, Richard, having come to the same realization a year earlier, had transferred to Berkeley from UC San Diego after our freshman year, and returned to the land of Disney with a grave affliction for which there was no cure. The symptoms were evident in his already impressive record collection: The Jethro Tull, Yes, Beatles, Rolling Stones, Crosby Stills & Nash, and Doors albums we had worn out the previous summer were still there, but suddenly a new section featured Aoxomoxoa, Anthem of the Sun, American Beauty, Workingman’s Dead, Live Dead, Wake of the Flood, and Europe ’72. But there was one particular double-album, affectionately known to Deadheads as Skull and Roses, that caused me to contract the same incurable infection to which my friend had fallen prey.

While this centerpiece of the Grateful Dead discography is loaded with great material, it was the NFA>GDTRFB (Not Fade Away into Goin’ Down the Road Feelin’ Bad) that knocked me off my feet. In fact, I fell so hard that by the time I got up I found I had immigrated from SoCal and was living in the Redwood forests of the UC Santa Cruz campus, studying sociology, learning to play the guitar, and looking and playing the part of a Hippie Deadhead – replete with tie-dyed shirts, long hair and patched jeans. And, of course, there were plenty of opportunities in the Bay Area to see the Grateful Dead, often after feeding my head with “Vitamin L.” My years in “La La Land” were firmly behind me, and there was “nothing left to do but smile, smile, smile.”

When faced with a confounding decision with lifelong implications, trust that you already have the wisdom you need to make the right call. The key to unlocking the answer is to locate that deep place of knowing and allow it to do its thing.

The Skull and Roses album was recorded in the Spring of ’71, during which the band played three nights at the Hammerstein Ballroom in Midtown Manhattan. The middle show, 4/5/71, included the NFA>GDTRFB that changed my life, and that show is my pick for T.W.I.G.D.H.

The great New York Yankees catcher, Lawrence Peter “Yogi” Berra – arguably the most accidentally quotable figure in American history – said:

When you come to a fork in the road, take it.

The humorous folly of this advisory is obvious: A “fork” in the road, by definition, represents a crossroads, and demands that a choice be made. Ergo the question: How can one simply “take it” when there are multiple options? Ambiguity notwithstanding, the wisdom in this advisory – whether intentional or inadvertent, as is the case with so many “Yogi-isms” (“You can observe a lot just by watching,” comes to mind) – requires further review. Luckily, we live in the era of slow-motion replay.

Think about the forks in the road you’ve confronted during your lifetime. Typically, one could be named, “Easy Street,” while the other might bear the moniker, “Risk Avenue.” As creatures of habit, we’re most comfortable “when life looks like Easy Street.” After all, the contours of that road are largely, if not completely known to us, so it appears to be the safest path forward. But in choosing to maintain the status quo in life, we invite the possibility – perhaps even the inevitability – that the street will turn into a circle or, worse, a dead end.

On the other hand, Risk Avenue represents the chance of “danger at your door.” But along with uncertainty comes an entire realm of intriguing possibilities that don’t come into the picture when we play it safe. Most of the choices we encounter in life fit these two descriptions, and the road not traveled – whichever one it is – might haunt us forever. So, how do we choose?

I doubt that Yogi Berra ever met world renowned author Dr. Spencer Johnson, author of the New York Times bestselling motivational business fable, “Who Moved My Cheese.” And I would bet my framed 1978 Closing of Winterland New Year’s Eve poster that neither saw the Grateful Dead. And yet, the answer to our dilemma lies in the synergy between Berra’s courage, Johnson’s nuanced understanding of the psychology of change, and this lyric from our concert of the week:

Goin’ down the road feelin’ bad.

Don’t wanna be treated this a-way.

Compare this to what Spencer Johnson says:

Change happens when the pain of staying the same becomes greater than the fear of change.

The song, Goin’ Down the Road Feelin’ Bad (also known as the Lonesome Road Blues) is a traditional American folk song that describes something fiercely fundamental about the human condition: the unquenchable desire for a better life. While the Grateful Dead made the tune their own and popularized it in a way that wasn’t possible when it was first recorded in 1923 by Appalachian singer Henry Whitter, its traditional nature creates a universal context applicable to anyone who has reached an intolerable level of pain and is willing to risk the unknown as the remedy.

Sooner or later, we all arrive at a moment when we have to draw a line as to how we will be treated, including how we treat ourselves. Having reached that point at the age of 20, I was feeling bad enough to leave the safe womb of Southern California and start a new life in the Redwood forests of Santa Cruz. I decided that “goin’ down the road” was the best way for me to treat myself, and although I will never know how my life would have unfolded if I had chosen otherwise, I know in the deepest part of my being that taking that chance was the right call.

When Yogi Berra instructed us about arriving at a fork in the road, his guidance wasn’t as vacuous as it sounds. His seemingly thoughtless conclusion to simply “take it” might leave us scratching our heads, given that an actual choice must be made. But urging us in the direction of taking a chance is in itself solid counsel.

More importantly, when faced with a confounding decision with lifelong implications, trust that you already have the wisdom you need to make the right call. The key to unlocking the answer is to locate that deep place of knowing and allow it to do its thing. If it takes some time to get there, be patient. Engage in the process, allow it to unfold, and the answer will reveal itself.

Think of a time in your life when you’ve faced a major decision with lasting consequences. How did you go about making that difficult choice? Did you act out of courage or fear? Chances are that acting courageously – going down Risk Avenue – worked out better for you than staying on Easy Street, and led to fewer regrets. After all, that fork in the road didn’t appear by pure coincidence. It’s there for a reason. Be like Yogi: Take it!

Concert of the week in Grateful Dead history: April 5, 1971 (Listen Now)

Subscribe and stay in touch.